Before

we look specifically at any of the three market structures in the title we

should take a closer look at revenue as this will be important in the analysis.

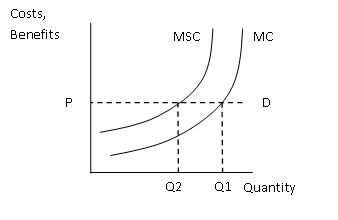

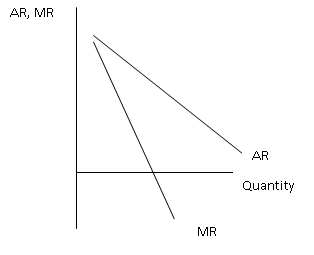

When price varies with output, which it does in all market structures bar

perfect competition, the demand curve is downwards sloping. Average revenue

equals (total revenue) / (quantity). This is the same as (price x quantity) /

quantity. Cancel out the two quantities and we're left with average revenue

being equal to price - hence it is equal to the demand curve.

So, the average revenue curve is sloping downwards

because it is equal to price. Why the position and shape of the marginal

revenue curve then? Well, as we know, marginal revenue is equal to the change

in total revenue divided by the change in quantity. If we substitute in price x

quantity for total revenue we are left with:

If we use the product rule to differentiate this (Google

this or find a text book, I'm not going to explain the pure math behind it) we're

left with marginal revenue being equal to:

The change in price over the change in quantity will give

us a negative figure, so what we're left with is Price + something negative.

Due to the "+ something negative" it will be falling below the AR

curve, hence its position on the diagram above.

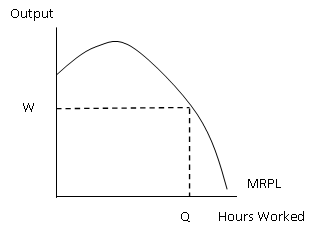

The total revenue curve interacts nicely with the marginal

revenue curve we can see above. The total revenue curve increases at a

decreasing rate. Why? Well, because to sell more the firm has to lower its

price. Due to this, there will come a point when total revenue is maximised.

This will coincide with the quantity at which marginal revenue is equal to 0.

That quantity will be the revenue maximising quantity for the firm.

Now that we've understood the concept of revenue, let us

hone in on the specific market structures. We'll start with monopoly. In a

monopoly we have one firm that dominates the market. How do they do this? It is

largely due to the barriers to entry into the market. They could be any of the

following:

·

Economies of scale.

·

Legal restrictions.

·

Aggressive tactics.

·

Product differentiation.

...the list does go on. These all make it very difficult

for new firms to break into the market and pose any sort of competition/threat

to the existing monopoly firm. Graphically, a monopoly looks as follows:

They produce at the point MC = MR because this is where

profits are maximised. At this point there is a difference between average

costs and average revenue, revenue exceeds costs which means that the monopoly

is making a supernormal profit. All pretty obvious thus far. Monopoly is

probably the easiest of the market structures to master, all there is to

remember is that supernormal profits are made in the long and in the short run.

To the consumer a monopoly may seem to be a disadvantage - higher prices and

lower output compared to perfect competition. This is true, but it does have its

advantages. Firstly, supernormal profits fuel innovation which can lead to

better, cheaper products in the long run. Secondly, if the economies of scale

are big enough then through a monopoly some markets can exist that wouldn't be

possible if monopolies weren't allowed. This is in the case of a natural

monopoly.

Natural monopolies are markets that have very high, fixed

start-up costs. So high that it becomes

unprofitable if more than one firm try and provide the good/service. An example

would be the London Underground - massive start up costs in laying the

foundations of the network. So, if there were two firms in the market a loss

would always be made and therefore production wouldn't occur at all. See this

diagram below.

If there was two firms trying to run versions of the

Underground simultaneously then neither would be able to stay afloat only serving

half of the market each - whereas one firm serving the whole market means it is

affordable. With two firms, the demand curve above with slope down at twice the

rate meaning it is always below the long run average costs curve, meaning a

loss will be made. The scale of production that comes with a natural monopoly

means that costs can be lower and therefore the market price can be something

consumers will be willing to pay.

That's the low down on monopolies. Now to move onto

monopolistic competition. Do not get the two confused - similar names yet

totally different market structures. In a monopolistic market firms sell a

different variety or different brand of the same product. There are many firms

that all act independently of each other with freedom of entry and exit into

the market. There is symmetry in the market - new firms entering the market

effect all old firms equally.

1 = Firm demand. 2= Firm demand after new competitor

enters.

Each firm has a share of the whole industry, but can only

influence the price minimally, hence the inelastic demand curve for the firm.

Every time a new firm enters the industry all existing firms will see their

demand decrease and the influence they have on industry price fall. Every new

firm that enters moves the market closer to perfect competition.

A firms profit in the short run looks strikingly similar

to that of a monopoly. Supernormal profits are available. However, emphasis on

'short term'. Over the longer term more firms enter and prices are forced down.

The quantity each firm supplies is also forced down and supernormal profits are

quashed. Firms will keep entering until average costs equal average revenue, at

this point no more supernormal profit is available. We haven't entered perfect

competition because the demand curve/average revenue curve is sloping downwards

meaning price is not constant across all firms.

|

|

On the left we have the firm in the short run. Supernormal

profit is made. The new firm enters and we move to the situation on the right

hand side. The firms individual demand has fallen, and thus its average revenue

and marginal revenue have fallen too. This means that the amount of profit that

is made has fallen. These firms will keep entering and this will keep happening

until supernormal profit is wiped out completely.

The model is all well and good taken at face value - but it

does have its limitations. In reality there is imperfect information about

profits and demand, it doesn't take into account the effect non-price

competition has and in reality it is difficult to identify an industry demand

curve. Bar all of these problems it does give us a fairly accurate

representation of a monopolistically competitive market. One problem with this

market type is because of the downwards sloping demand curve - production will

not take place at the lowest long run average cost. Therefore monopolistic

competition isn't as efficient as perfect competition.

The final type of market structure to analyse is that of an

oligopoly market. Oligopoly is when there are a few large, major players in an

industry. 3 or 4, for instance. There are significant barriers to entry and

firms are very interdependent. The firms have to look at the incentives to

compete with the other dominant firms and the incentives to collude with these

firms to determine their plan of action.

Now, to determine the total production of an oligopoly

market we have to run through a little story. We start with an industry with

one firm acting as a monopoly. The firms demand function is as follows: P = 200

- Q and its marginal costs are 0.From this, we can see that if quantity was 0

then price would be 200 and if price was 0 then the quantity would be 200. We

can use this to draw an initial demand curve.

We derive the marginal revenue curve by differentiating

total revenue. Total revenue = (200-Q) x Q, and that differentiated leaves us

with: MR = 200-2Q. Profit is maximised at MC=MR, and MC = 0, so therefore the

firm will produce 100 of the good. Half the market is supplied.

Now, the next part of the story is for a competitor to enter

the market. Firm B spots that there is unfulfilled demand, 100 of it, and

decides to enter the market. The demand curve for Firm B is going to be: P =

100 -Q. With that as the demand curve, and using the method in the paragraph

above, firm B works out it's marginal revenue curve to be: MR = 100 - 2Q. The

new market now looks like this:

Firm A is still supplying 100 of the market and now Firm B

has entered and is supplying an additional 50 to the market. 150 of the market

demand is satisfied.

But, the next day Firm A reacts to this new firm. They have

to readjust and now see their demand function as: P = 200 - Q - 50, or P = 150

- Q.

Both Firm A's demand and MR curves have swung in, and now

it finds itself supplying only 75 to the market compared to the 100 it was

supplying previously. The new entrant has brought down Firm A's production. 125

of the market is now supplied.

Firm B has to react to this change from Firm A. It sees

Firm A's new supply of 75 and recalculates its demand function to be: P=200 - Q

- 75, or P = 125 - Q. From this it gets its marginal revenue to be: MR = 125 -

2Q. At this marginal revenue Firm B will now increase its production to 62.5.

137.5 of the market demand is now satisfied. You may have noticed some

repetition here. The market will keep going back and forth between the two

until an equilibrium is achieved. Firm B's production increases whilst Firm A's

falls. So when will equilibrium occur? It will be the point when one firm

reacts to another firms level of supply and achieves the same level of supply.

In the example above this is when 66.66 is produced by each firm, leaving the

133.33 of the market demand being satisfied.

What we have described above is typical when the number

of firms in an industry is small - it is known as Cournot competition,

competing over market share. As we see above, with 2 firms in the market each

firm supplies 1/3 of the total demand in equilibrium meaning 2/3 of demand is

satisfied. With 3 firms in the industry, each firm will supply 1/4 of the total

demand in equilibrium meaning 3/4 of demand is satisfied. Each additional firm

added means more of the total demand is satisfied and therefore the market is

moving closer to perfect competition.

What can we say about profits under Cournot competition?

Well with the total demand function being P = 200-2(Q) we can calculate price

to be 66.66 by substituting in the equilibrium quantity we derived earlier. We

assumed costs are nothing, therefore total revenue in the industry will equal

2(66.66 x 66.66) = 8887.7. Sounds like a nice figure. However, what would it be

under a monopoly? We saw Price and quantity equal to 100 when there was just

one firm, so total revenue will be 100x100 = 10,000. Higher than in the

oligopoly. This tells us that firms would be better off if they got together

and agreed to limit the market - this is known as collusion.

Collusion can happen in many ways, one of these being

price leadership by the dominant firm. In this scenario, the dominant firm

makes an assumption that all the smaller firms in the industry will act like a

firm in a perfectly competitive market once it has set the price and chosen its

output.

The dominant firm has to decide the price it is going to

charge. The price has to be between the range of P1 and P2 above. Any higher

than P1 and there will be excess supply, any less than P2 and they won't be

able to afford to supply anything. So, the demand curve for the dominant firm

runs from P1 down to the point on the market demand curve that coincides with

P2. So, the leader can choose a price, say P. Then, with a price decided the

dominant firm has to decide how much it will produce at this point and

therefore how much of the market is left for the other smaller firms.

So, Price P was decided by the leading firm. Therefore,

at this price the dominant firm will supply QL to the market (Where P =

Dominant firm demand). The following firms will supply QF to the market (Where

P = S) and the total supplied to the market will be QT. QT should be QL + QF. That

is one form of collusion between firms - a very subtle one and therefore very

difficult to prove.

A few rules of thumb are used when it comes to tacit

collusion - using an average cost mark-up when it comes to pricing, for

example. Something like P = (1 + 0.1)AC would do the trick. Firms would agree

on a certain rate of profit and then enforce this pricing mark up to achieve

that. They also use benchmark pricing, £9.99 or £14.99 for example.

As far as collusion and the law goes it's a tricky one.

It is illegal but it can be incredibly difficult to prove that it is actually

going on. It is entirely up to the authorities to decide the difference between

prices being set competitively and firms agreeing prices. Unless it is really

bad or really obvious it rarely gets proved.

Phew, that is it. Cheers for reading guys. Same script -

comment if you need any additional help or you spot mistakes, all feedback is

welcome!

Sam.